I was an 18-year-old summer intern just finishing my sixth week at The Times-Picayune when the Up Stairs fire seared into my consciousness horrific images of 32 people burned alive on the night of June 24, 1973.

I’ll never forget the sights and sounds of the scene at Chartres and Iberville streets, the smell of soot and burnt flesh, or the emotional trauma of those who escaped the inferno, only to learn that some of their closest friends had perished.

Now, 50 years later, I look back at the fire’s aftermath with mixed emotions. Part of me marvels at how far we’ve come as a society — gays and lesbians can proudly celebrate who they are and marry those whom they love. Another part of me cringes at how often trans people face violence, harassment and government-sanctioned condemnation.

Such thoughts were far from my mind that long-ago night. As I hurried toward the blaze, I had no idea how dramatically what I was about to witness would change New Orleans. And me.

The first thing I saw there stopped me cold. A man with much of his flesh burned off sat on the curb across from the Up Stairs Lounge, weeping and begging for help. His pain was so gut-wrenching, I had to turn away.

That’s when I saw the Up Stairs Lounge engulfed in flames and smoke — and a man pressed against the bars of a window, his hair and flesh nearly burned off, one arm hanging through metal bars that had prevented his escape to safety.

This time I could not turn away. I stared at him, wondering who would put bars on a second-story window, and who was this man whose final, desperate moments would capture in one ghastly picture the tragedy that was the Up Stairs fire.

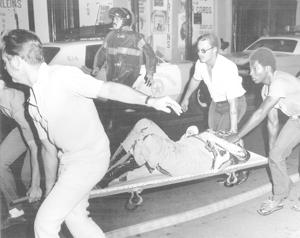

A senior reporter grabbed my arm and brought me back to the moment. My assignment now was to write a “sidebar” story about the scene at Charity Hospital. I don’t remember how I got to Charity, but once inside the frantic ER, I had a front-row view of tragedy — and heroism.

Nurses and doctors valiantly attended victim after victim, putting gauze and salve on the bodies of badly burned men who moaned in what I can only describe as haunting tones. Many of the victims wept.

One nurse gently tried to peel back a man’s burnt skin before wrapping him as he pleaded for something to deaden his pain. Some of those who managed to escape the deadly inferno showed up, offering information about injured friends and asking about others whose fates remained unknown.

I stayed in the ER for about an hour, long enough to get a mental picture that I hurriedly put into a story. Then as now, the rush to get a big story into print or on the air forces reporters to detach from the emotional immediacy of a tragic event. We call that detachment “objectivity,” a skill-set that we cultivate — but one that costs us a piece of our humanity every time we rely on it.

I was just beginning to learn that skill set in June 1973, but I’ve never been able to detach from the Up Stairs fire.

Every time I smell soot, I think about the man I saw on the curb crying in pain, or the man who died pressed against the bars of that second-story window. Years later, I learned that the man in the window was the Rev. Bill Larson, the beloved pastor of the Metropolitan Community Church, which ministered to the LGBTQ community.

It was also years later that I realized how profoundly the Up Stairs fire changed the local gay community. In the immediate aftermath of that tragedy, the practiced indifference (or worse, the hostility) that many New Orleanians harbored towards the LGBTQ community quickly came to the fore — and stayed there far too long.

That June night, I mostly felt an incomprehensible mixture of numbness and shock. The next day, when my girlfriend nervously asked me about the fire, I couldn’t find the words to express how I felt. I just hugged her. And in that moment, I finally cried.

My tears dried a long time ago, but the tears of those who lost loved ones in the Up Stairs fire have yet to dry. I hold out hope that, as New Orleans looks back 50 years later, sincere expressions of support and empathy will finally — finally — dry those tears.

Leave a Reply