OMAHA, Neb. — The best hitter in college baseball starts his swing by arching his back. He straightens when the pitcher winds up, then cocks his hands as he shifts onto his right foot and bends into a squat. The rest of the motion happens in an instant. Dylan Crews plants his front foot, pushes forward and whips the bat around his body.

Few college baseball players have ever swung with his combination of speed, power and consistent precision. Almost always in perfect sequence, LSU’s junior center fielder uncoils through his strong lower half like a rubber band, creating rotational force and acceleration that pounds opposite-field home runs and zips ground balls through the infield.

This unique swing helped make Crews the projected No. 1 pick in next month’s MLB Draft and arguably the most talented player in team history. It would be one thing to hit for power or contact. Crews does both. He owns a career .696 slugging percentage, and he’s batting .434 as the Tigers enter the College World Series, three points above LSU’s single-season record.

“I call him a perfectly built baseball player,” LSU coach Jay Johnson said. “He’s tapping into every ounce of his body to generate the bat speed and the power. He does it better than a lot of big league hitters do right now. I’ve very rarely seen it — if I’ve ever seen it — at the college level.”

Unless asked, Crews does not ponder the technical aspects of his swing. He relies on the way he feels to maintain it. He wants his lower body to start first, then keep his upper half square to home plate, building from the ground up. If he senses an issue, he works until he is hitting up the middle with backspin and driving balls from left- to right-center field.

Though Crews does not lean on analytics, there is tangible data that explains what separates him from everyone else. He has undergone visual, cognitive and horsepower tests during his LSU career. The results illustrate a swing designed for hitting baseballs — and suggest his success should continue at the next level.

“When you’re that high on a lot of these markers,” LSU director of performance innovation Jack Marucci said, “it’s tough not to say this guy is a no-brainer.”

Start with the eyes

During preseason practice Crews’ sophomore year, LSU conducted a visual test that has become a staple within its teams. The exam gauges ocular dominance by measuring pupil stimulation, pinpointing which eye absorbs the most information for the brain to process.

Crews’ results showed no imbalances. He was essentially dominant in both.

“He’s going to pick it up from a left-hander and a right-hander,” Marucci said. “If it’s coming in backside, he should be able to pick it up. He should be able to pick it up if it’s tight inside. And that’s rare.”

Marucci, formerly LSU’s director of athletic training, had spent years around major league hitters through Marucci Sports, the equipment company he once started out of his backyard tool shed. He talked to them about their approach, pitches they look for, which part of the field they use and how they see the ball.

The conversations sparked Marucci’s fascinations. He started working with Mike Mann, a former college volleyball player who launched a company devoted to understanding how vision affects athletes’ decision-making. They tested LSU football pass-catchers before the 2019 season. Later, they examined the baseball team.

“There’s a correlation between our best hitters and how they score on that stuff,” Johnson said.

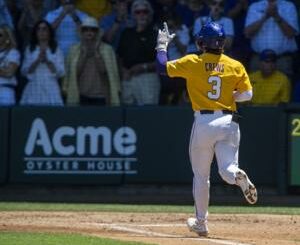

LSU center fielder Dylan Crews (3) bats during batting practice before first pitch against Kentucky, Thursday, April 13, 2023, in an SEC matchup at Alex Box Stadium on the campus of LSU in Baton Rouge, La.

For hitters, the results help predict how they should perform against certain pitchers. Marucci said right-handed batters with left-eye dominance have more success against right-handed pitchers, contrary to popular belief. But Crews saw everything well. He was comparable to elite athletes across multiple sports.

“ ‘I don’t know who Dylan Crews is,’ ” Marucci recalled Mann saying, “ ‘but he’s way off the chart.’ ”

Crews’ vision lets him find clues in the moments before he swings. Sometimes he notices a pitcher tipping what he’ll throw or hints in the position of an arm angle. Then, through years of ongoing practice, he sees the differences in spin as various pitches hurtle toward him.

Hitters have roughly .25 seconds to identify a 90 mph fastball. Crews’ sight gives him an essential split-second of extra time. He can let the pitch travel a few feet further, helping him separate balls from strikes, then hammer blasts to the opposite field.

All this despite the fact that he rarely gets good pitches to hit, testing his patience and making him wait for one he can drive.

“What’s great about his eyes is he can pick up the mistake, and when somebody tries to challenge him, he makes them pay,” Johnson said. “He does that better than any hitter that I’ve ever seen.”

A process within the brain

Sometimes in the middle of games, Johnson looks over and sees Crews along the dugout rail, deep in thought and steadying his breath. Johnson teaches visualization, and Crews has taken to the method. Between plate appearances, he looks for tendencies and imagines what he’ll do next, forming a plan in his head.

Crews’ brain is wired for baseball. He has a steady, relaxed disposition. Not much rattles him or makes him overly excited. And he has come to understand the sport contains unavoidable failures. As much as he wants to, he knows he will not reach base every time.

As expectations of him rose, Crews worked on the mental part of the game. He likes to get away by fishing or relaxing with friends. He can compartmentalize so he doesn’t feel overwhelmed, and he thinks his approach will separate him when talent gaps shrink.

“I’ve learned a lot in college, learning how to accept failures and move on to the next one,” Crews said. “That’s been huge for me. And also creating a balance throughout not just baseball, but my life. Doing stuff I enjoy outside of baseball allows me to reset my mind.”

Once he steps back into the batter’s box, Crews’ brain creates another advantage.

LSU center fielder Dylan Crews (3) bats on opening day against Western Michigan, Friday, February 17, 2023, at Alex Box Stadium on the campus of LSU in Baton Rouge, La.

In February 2021, he underwent the S2 Cognition test. Created by two neuroscientists, the evaluation measures how athletes process information and make split-second decisions. It has been used by LSU football for about nine years and the baseball team for the last two-and-a-half, particularly once Johnson arrived.

Hitters get tested on several categories, including perception speed, trajectory estimation and impulse control. In milliseconds, they have to recognize the pitch and predict where it will cross the plate, then decide whether or not to swing. Players process the information at different rates.

S2 co-founder Scott Wylie said the company has tested almost 300 minor leaguers who later reached the majors. More than 50% of them scored above 80% on the test, the highest percentile.

Wylie declined to reveal Crews’ scores, saying LSU did not want them released before the draft, but added “he fits right in there.” Others with knowledge of Crews’ scores talk about them as some of the highest in the history of the test.

“At this aspect of performance, Dylan is at an incredible advantage,” Wylie said. “Undoubtedly, that is contributing to what you’re seeing on the field. He sees and processes things faster than most human beings on the planet.”

But Wylie compares elite players to a Ferrari. Even though the car has a high-powered engine, the driver has to know how to operate the machine. Crews, he says, can handle the sports car that is his body.

‘One of our elite football players’

Before Crews ever played a college game, he visited the Baseball Performance Lab in Baton Rouge. The company has changed the way players choose their bats while studying the relationship between hitters and equipment. Crews tested wooden and metal bats as he prepared for a higher level.

During the evaluation, the BPL measures how much horsepower a player creates through their lower body, core and upper body. Crews reached 41 inches in the vertical jump. He did a sit-up and tossed a medicine ball 26 feet 11 inches. He threw the medicine ball again 26 feet 3 inches in the upper body test.

The numbers topped major league averages and compared to All-Stars at the time. Three years later, Crews’ total score as an incoming freshman is the third-highest in the history of the horsepower test, sandwiched between current major leaguers Josh Lowe and Trevor Story.

“It’s so hard to find anybody that has that kind of core and upper body power that also jumps that high,” said BPL director of player development Micah Gibbs, a former LSU catcher and hitting coach.

Marucci later saw the jump data. He has collected similar numbers for years from the football team, and Crews matched the program’s best defensive backs and wide receivers over the past five or six seasons. Gibbs suspects Crews’ vertical jump has gone down because he would otherwise create too much lift.

“He would be considered one of our elite football players,” Marucci said.

LSU outfielder Dylan Crews (3) hits a home run against Arkansas in the fifth inning of the first game of a doubleheader on Saturday, March 25, 2023 at Alex Box Stadium in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. LSU defeated Arkansas 12-2.

This year, for the first time in his LSU career, Crews focused his workouts on explosion. He used to squat 465 pounds, but he stays between 220 to 285 these days, trying instead to stand as fast as possible. The method improved his overall speed, helping him as a base runner and defender, and possibly added more explosion to his muscular legs.

Crews’ swing starts with this strong lower half. He puts his front foot down, then transfers his weight forward, creating a kinetic link that draws from the ground. His back knee bends, and as he rotates, Crews separates his hips and shoulders so his upper half stays square to home plate. His hands finally come through like a slingshot, delivering the force of his entire body through the ball.

The sequence generates speed and power. An SEC West assistant who recruited Crews in high school said he had never seen a player with such fast bat speed. Entering the Baton Rouge regional, his average exit velocity this season was 95.4 mph.

The combination lets Crews catch up to the balls that he lets travel deeper into the strike zone and unload on them.

“I’ve always called him the best recovery hitter that I’ve ever seen,” Johnson said. “What that means is you don’t even think he’s going to swing. The ball looks like it’s beating him. Then bam, he’s taking it out of the catcher’s glove and hitting a homer or double to right.”

The complete puzzle

Sometimes, Gibbs talks to major league staffers and they start comparing Crews to other players. Andrew McCutchen, a five-time All-Star, comes up. Mike Trout, a future Hall of Famer, gets mentioned.

But most of the players with similar explosiveness and speed don’t have Crews’ strength. And a lot of the ones with his physical tools lack the cognitive ability and vision.

The comparisons linger, unanswered.

“It’s unheard of, so it’s hard to say,” Gibbs said. “Who does he compare to? Well, there hasn’t really been anybody to compare him to.”

As much as Crews has already developed, he is trying to improve. His diagonal swing path makes him vulnerable to high fastballs. He worked with Johnson on plate discipline during the offseason, and he has since drawn a career-high 65 walks while reducing his strikeouts.

He still wants to see the ball better, too. Before every game, Crews hits off a high-spin machine that spits out random pitches.

“I have failed a lot,” Crews said. “That thing has carved me up a lot of times, but it has definitely helped me out for sure. It slowed the game down going onto the field.”

LSU center fielder Dylan Crews (3) drives the ball for a hit against Mississippi State in the fourth inning on Sunday, May 14, 2023 at Alex Box Stadium in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Mississippi State defeated LSU 14-13 in 10 innings.

Then he steps into the box, the mechanical thoughts melt away and Crews separates himself from everyone else.

A lot of talented college hitters, Johnson said, possess a skill or two that makes them successful. Crews has a handful, and none of them account for his defense, arm strength and character, the thing so many around LSU say truly sets him apart.

“You have great players, but when you pair the great player with Dylan Crews’ character, you get Dylan Crews,” Johnson said. “That doesn’t come along very often.”

Crews now plays in the College World Series for the first time. He wanted to win a national championship since he bypassed the draft out of high school, and LSU has a chance after winning five straight games in the NCAA tournament. Whenever the run ends, Crews will begin a seemingly limitless professional career.

Before the season, Marucci called the Pittsburgh Pirates’ director of scouting. He grew up around Pittsburgh, and his hometown team has the first pick in the draft. Marucci had watched Crews for two years. He understood the unique swing.

“Let me tell you,” Marucci told the scouting director, “about this guy we got here.”

Leave a Reply