The French royal namesakes of our city and state — Philippe II, the Duke of Orleans, and King Louis XV — never set foot in what would become New Orleans or Louisiana.

But a great-grandson of Philippe II — Louis-Philippe, who was born in 1773 and became king of the French in 1830 — did both, during a circuitous tour in the late 1790s.

His travels bring to mind those of other French aristocrats who toured and assessed the new American nation in this era. But Louis-Phillipe’s visit began not as an inquiry but an exile, and in retrospect, he was biding his time as much as being inquisitive.

As a royal, Louis-Phillipe found himself in a precarious position at the outbreak of the French Revolution. Historian Henry Steele Commager wrote that the young prince “had tried, briefly, to accommodate himself to the Revolution,” joining the Jacobins and serving as a lieutenant general.

But he stridently opposed the Republic’s decision to execute King Louis XVI in 1793, a policy that eventually sent his own father to the guillotine, at which point the title of Duke of Orleans — held two generations earlier by the namesake of New Orleans — passed to Louis-Phillipe.

Unsure of his own fate, Louis-Phillipe fled to Switzerland, Germany, Denmark and Norway. He eventually joined up with his two brothers, the 22-year-old Duke of Montpensier and the 17-year-old Count of Beaujolais, and made plans to flee to America.

Bearing Danish passports and pockets full of cash, the three brothers made their way individually across the Atlantic and “met in Philadelphia,” wrote Commanger, “in time to witness the inauguration of John Adams to the presidency” in March 1797.

Romance and curiosity

Louis-Phillipe reveled in the excitement of what was then the political and cultural center of the United States, hobnobbing with elites and dabbling in l’amour with a banker’s daughter. A souring of that liaison led Louise-Phillipe to trade romance for “romantic curiosity” and go see the country.

Having splurged a thousand dollars on horses and tack, the three young princes — without a kingdom, but with a valet — donned buckskin breeches and departed on the 1790s version of the American road trip. “But in their saddlebags,” noted historian Morris Bishop in an American Heritage article, “they carried white satin suits with lace ruffles.”

Off galloped the threesome, to places like Baltimore; Wilmington, Deleware; and the nation’s new capital of Washington, D.C., under construction at the time. (“I fear that its architecture will appear heavy when the scaffolding is removed,” wrote Louis-Phillipe of the White House; “the front entrance seems to me ridiculously small.”)

After visiting Georgetown and learning of its residents’ jealous view of the rising new capitol, the three princes headed down the “Potowamack” (Potomac) River to pay their regards to former President George Washington.

It was there at Mount Vernon that Louis-Phillipe expressed his disdain for slavery, seeing “about 400 blacks scattered among the different farms” belonging to the father of the American nation.

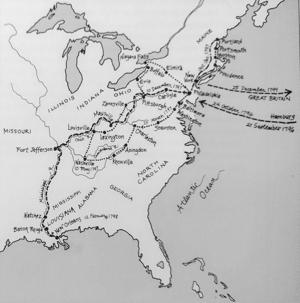

As for the former president, the courtly Virginian welcomed the trois frères and, upon hearing their interest in exploration, traced out a suggested itinerary on a map. “Years later,” wrote Bishop, “King Louis Philippe liked to impress American visitors by unfolding his map and pointing to the red line drawn by the hand of the great Washington.”

Plucky people, bad coffee

The route took the Frenchmen over the Montagnes Bleues — the Blue Ridge Mountains — where settlers were fewer, forests prevailed over fields, and the western frontier beckoned.

While they readily used their pedigree to gain access to better accommodations, the brothers mostly stayed at rustic inns and embraced ordinary Americans, who called them “Mr. Orleans,” “Mr. Montpensier” and “Mr. Beaujolais.”

Like other visiting French elites, Louis-Phillipe came to admire Americans for their spirit and pluck, though he did not hesitate to critique. He recoiled at frontier fare, which, while served with hospitality, typically ran along the lines of “fried fatback and cornbread” accompanied by “coffee everywhere, but bad, very weak.”

Through Knoxville and Maryville, Tennessee, they rode, past the Smoky Mountains and through Native territory, where Louis-Phillipe eagerly documented details of Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw and Chickasaw cultures.

On to Kentucky

In May 1797, the brothers veered westward to Nashville and north to Bardstown in Kentucky, where it is said that, many years later, Louis-Philippe gifted the town’s Catholic Church with paintings and a clock still inside.

Alas, that is where Louis-Philippe’s diary ends, subsequent volumes having been lost. But we can continue the voyage courtesy of “Mr. Montepensier,” the middle brother, who later recounted the next leg and sketched a number of scenes.

After leaving Bardstown, the brothers “relaxed for several days in Pittsbourg,” made their way to Niagara Falls, “cascade[ing] from a prodigious height,” and proceeded throughout New England.

But while in Boston, they happened upon alarming news: their mother, the Duchesse of Orleans, long viewed suspiciously on account of her kin, had herself gotten deported from France to Spain.

The brothers resolved to join her, “but there was a difficulty,” wrote Bishop. “England and Spain were at war, and communications between America and Spain were cut off. The princes saw only one possibility — to make their way to New Orleans, then held by the Spanish, and embark on a Spanish blockade-runner.”

Meeting a young Marigny

In December, the trio made their way to Pittsburgh, hired a keelboat and sailed down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. After dodging snags, shoals, bandits, ice and frigid temperatures, they docked at New Orleans on Feb. 17, 1798.

The city’s Creoles, who tended to be outspoken supporters of all things French in spite of their Spanish governance, welcomed the exiled Bourbons with open arms. The Marigny family, epitome of the Creole elite, regaled the princes at their plantation mansion at what is now the foot of Elysian Fields Avenue, and pressed a loan upon the brothers to aid their quest to restore their status.

According to the historian Commager, it was Bernard Marigny who advanced the loan, though he was only 12 at the time. Later writers have viewed this regal encounter as having transformed the youth into the lordly bonvivant we remember today, founder of the Faubourg Marigny.

According to another proud French Creole, Charles Gayarré, the three brothers also paid a visit to the plantation of Gayarré’s famed grandfather, Etienne de Boré, known for his 1795 experiments to granulate Louisiana sugar cane juice.

“In the beginning of 1798,” wrote Gayarré, “the Boré plantation was visited by three illustrious strangers, the Duke of Orleans and his two brothers, the Count of Beaujolais and the Duke of Montpensier, of the royal house of France, who, driven into exile after the death of their father on the scaffold, were striking examples of those remarkable vicissitudes of fortune. … Little did (Etienne) de Boré dream that the day would come when three princes of the blood would be his guests on the bank of the Mississippi.”

The guests would have landed at what is now Henry Clay Avenue off Tchoupitoulas Street, where Children’s Hospital now stands, and proceeded on to Boré’s house farther up Henry Clay, near present-day Magazine Street.

The succor they received in New Orleans buoyed the Bourbon brothers as they departed for Havana, where according to Commager, “they received a splendid welcome” for sharing “the same blood as Philip V,” the former Bourbon king of Spain.

Viewed with suspicion

Spanish authorities, however, viewed them nervously and ordered them expelled from Cuba. Another exile ensued, this one more harrowing than romantic, and after hopscotching around the Atlantic basin, they ended up in England in 1800.

Life’s vicissitudes only intensified. Montpensier and Beaujolais both died young of tuberculosis, while Louis-Phillipe managed to stay healthy and pay off his debts (including to Marigny, in 1813). He married his way back into a regal position in Sicily, which enabled him to return to France during the Bourbon Restoration.

The July Revolution of 1830 set the stage for Louis-Philippe to ascend to the throne, becoming King Louis-Philippe I of France — a remarkable redemption for a man who once slept three in a bed at a Tennessee tavern, and had to relieve himself out a window for want of a chamber pot.

King Louis-Philippe’s reign was hardly illustrious, but he at least eschewed the sort of ostentation that breeds resentment. He long remembered his American supporters, among them Marigny, who, according to the Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Louisiana (1892), “was handsomely received and entertained” by the king in Paris in 1830. “On his return to New Orleans,” they noted, Marigny “repeated many of the jokes, witticisms and conundrums which occurred at the royal board.”

A road trip remembered

As for King Louis-Phillipe I, “he gave France eighteen years of peace and prosperity,” opined Bishop, “but in the end his people wearied of peace and prosperity,” and during the 1848 Revolution, insurgents drove him into one final exile, in England, where he died in 1850.

France’s last king had his share of faults, but he partly credited his many attributes to his long-ago American road trip. “My three years’ residence in America,” he wrote, “have had a great influence on my political opinions and on my judgment of the course of human affairs.”

His journals were discovered in a London bank safe in 1955, translated to English by Stephen Becker, edited by Commager, and published in 1977 under the title “Diary of My Travels in America: Louis-Philippe, King of France, 1830-1848.”

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of “Draining New Orleans; “The West Bank of Greater New Orleans,” “Bienville’s Dilemma,” and “Bourbon Street: A History.” Campanella may be reached at http://richcampanella.com, rcampane@tulane.edu, or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Leave a Reply